(Travelers wait in a crowded Beijing train station during the Lunar New Year. Image: Hung Chung Chih/Shutterstock.)

If you think the traffic we have around Thanksgiving or Christmas is daunting, just imagine how the hundreds of millions of Chinese who are headed home for the Spring Festival (a/k/a the Lunar New Year) must feel.

While the first day of the Lunar New Year falls on February 5 this year, January 21 marked the start of Chunyun (春运; Chūnyùn), or the Spring Festival travel rush. Every year, beginning 15 days before the Lunar New Year, many of China’s urban areas empty out as residents return to their hometowns to usher in the new year--Beijing alone sees an annual exodus of over eight million people, or 40% of its population.

Then, after a week-long national holiday, the traffic reverses itself as people start to return to work and school. Roads and railways remain crowded until well after the national holiday ends, since many people choose to extend their vacation and college students get a longer break. All told, the whole Chunyun period lasts for approximately 40 days. This year, the travel rush is expected to last until March 1.

So if you’re thinking Spring Festival seems like a good time to travel, here’s why you might want to reconsider. At the very least, it’s best to know what you’re getting into.

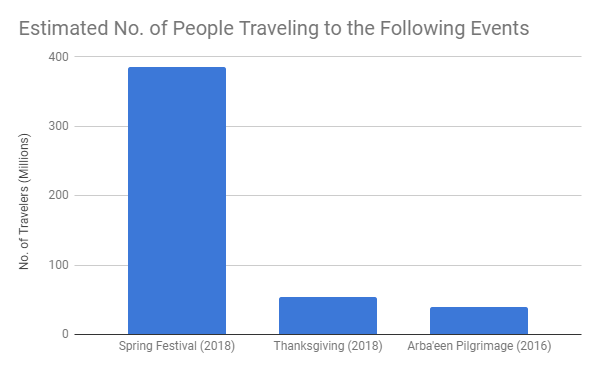

The Largest Mass Migration on Earth

(Source data: Statista)

Chunyun is the largest annual human migration on Earth, dwarfing every other major migration and travel event. In 2018, an estimated 385 million people traveled for the Spring Festival--that’s more than the entire population of the United States. In comparison, just 54 million people traveled for American Thanksgiving, and 40 million for the annual Arba’deen Pilgrimage in Iraq.

While Chunyun refers to the Spring Festival travel season in mainland China, the same phenomenon is also observed in other parts of East Asia where the lunar new year is celebrated, such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and South Korea.

Everyone Has Places to Be

Why do so many people travel around this time of year?

For many Chinese people, it is a long-held tradition to travel to their hometown and reunite with their families for the Spring Festival. Historically, in mainland China, this usually meant traveling across town, or a few towns over, since many peasants were tied to land and did not move far from where they were born. This continued even after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, when a nationwide hùkǒu (户口) system, or household registration system, restricted where people were allowed to live, limiting internal migration within the country.

After economic reforms in the 1980s, however, many new economic opportunities emerged, especially in cities along the eastern seaboard, and restrictions on people’s mobility were loosened. Millions of migrant workers left their hometowns in the countryside and streamed into the cities to work. According to some estimates, there are over 275 million migrant workers in mainland China today, and for many of them, the Spring Festival is the only time they can return home.

(A migrant worker returns home from Guangzhou for the Spring Festival. Image: GuoZhangHua/Shutterstock.)

In recent decades, the number of university students studying outside of their hometowns has also increased. Since winter break is timed around the Spring Festival, many students return home to spend the holidays with their family and friends.

Finally, since Spring Festival coincides with one of two week-long public holidays (the other being the National Day Golden Week in October), growing numbers of Chinese are choosing to travel for pleasure during this period. Popular domestic tourist destinations include Hainan, Yunnan, Guangdong, and Fujian, which tend to be balmy this time of year.

What makes traveling during Chunyun difficult?

(Passengers wait in line to have their tickets checked before boarding the train in Mianyang. Image: dailin/Shutterstock)

As you can imagine, Chunyun puts enormous strain on China’s passenger transportation systems. Last year, China logged 3 billion individual trips by land, air, and water during the 40-day period. Since air travel remains too expensive for most of China’s middle class, the railway and road networks bear most of the brunt of this traffic.

The first hurdle those traveling by train must face is simply obtaining tickets. Due to high demand, train tickets sell out weeks in advance, sometimes in a matter of minutes after they go on sale. The Chinese government has adopted measures to ease the congestion, such as adding more temporary trains (临时客车 línshí kèchē, or 临客 línkè for short) and relaxing the return policy for tickets. Most importantly, in 2010, a “real-name and ID” requirement was instituted to prevent scalpers, known as 票贩子 (piào fànzi) or 黄牛 (huáng niú; lit. “yellow cows”), from buying up tickets and selling them at inflated prices.

Unfortunately, some scalpers have found a way around this, using stolen personal details and “ticket-snatching” plug-ins to rapidly buy up tickets online. Then, once they find an interested buyer, they refund and immediately repurchase tickets in the buyer’s name, who pays a premium for the “service.”

Safety issues are also exacerbated during the travel rush. While trains in China almost always allow for a certain number of standing tickets, during the Spring Festival, overcrowding on trains is common, and rail cars are sometimes so full that passengers are forced to stand in the lavatories. On China’s highways, overworked bus drivers contribute to higher-than-normal accident rates.

(Constant vigilance. Image: joyfull/Shutterstock.)

Chunyun is also prime time for thieves and pickpockets, who take advantage of packed stations and prey on tired, stressed travelers who leave their belongings unattended. Theft is especially prevalent leading up to the new year, when thieves, like everyone else, are faced with the prospect of doling out red envelopes stuffed with cash to their younger relatives.

(Flight delays galore. Image: atiger/Shutterstock.)

During the Chunyun period, inclement weather can paralyze China’s transport systems. The sheer number of travelers makes it hard to deal with delays and cancellations because there are very few empty seats in which to put stranded travelers, leading to simmering tempers and even violent incidents. In 2014, after heavy snowfall disrupted flights in and out of an airport in Zhengzhou for days, angry passengers rioted, destroying computers and attacking airline staff.

Stay Home, Get Creative, or Suck It Up

So how do people cope with Chunyun?

Some simply avoid it altogether. The expense and difficulty of returning home for the holidays are just two of many reasons some people choose to 躲年 (duǒ nián), or “escape Spring Festival,” a growing phenomenon in recent years. By forgoing the trip home, they can avoid some of the financial and emotional pressures surrounding the new year.

Others are exploring alternative travel arrangements. Many young people are turning to social media to arrange carpools (拼车 pīn chē) with friends and even strangers because it is relatively cheap and convenient. International travel is also increasingly popular; in 2018, 6.5 million Chinese people traveled overseas during the Spring Festival, representing a nearly 6% increase over the previous year.

For most, however, Chunyun is simply part and parcel of the Spring Festival. In the same way many Americans resign themselves to slogging through hours of traffic to go see Grandma on Thanksgiving, many Chinese people are willing to battle the crowds at the bus depot, train station, or airport. The reward of spending the Spring Festival with their loved ones makes it all worth it.

Comments