One of the first decisions any student of Chinese must make is whether to learn simplified or traditional Chinese characters. Sometimes this choice is made for you by a teacher or a parent, but in other cases you may have to decide for yourself.

To help guide your decision-making, we’ve answered some of the most frequently asked questions about the differences between simplified and traditional Chinese characters--with a few helpful language learning tips and fascinating cultural tidbits thrown in, of course!

Q: Why are there two different sets of Chinese characters?

Over the course of history, written Chinese has always changed constantly. Since the earliest Chinese characters in the late second millennium BCE were carved into animal bones and turtle shells, countless characters have fallen in and out of use, and strokes have been added and removed.

In the early 1900s, Chinese intellectuals began to look for ways to modernize China. Some of them saw the Chinese writing system as a sign of China’s backwardness and began to call for the system to be reformed or even abolished. Lu Xun, one of the most celebrated Chinese writers of modern times, once wrote that, “If Chinese characters are not destroyed, then China will die (漢字不滅,中國必亡; or, if you prefer, 汉字不灭,中国必亡; hànzì búmiè, Zhōngguó bì wáng).”

(Image: Lu Xun, leading Chinese literary figure and a master of irony.)

In the 1950s, as part of a campaign to raise the national literacy rate, the Chinese government set out to simplify some of the most complex characters, resulting in a divide between 繁体字 (fántǐzì, traditional characters, lit. “complex characters”) and 简体字 (jiǎntǐzì, simplified characters). Singapore and Malaysia also created their own sets of simplified characters which are identical to simplified characters in use in Mainland China.

Fun fact: the English term “traditional characters” was brought into common usage by Cheng & Tsui in the 1980s, when we published the first Chinese language textbooks to use both character sets!

Q: How did reformers decide which Chinese characters to simplify?

Reformers had two goals: to reduce the total number of characters in use, and to make the remaining characters easier to write.

To that end, reformers first eliminated many variant characters--that is, characters that have the same pronunciation and meaning but look different. In many cases, reformers chose one character (usually the simplest one) and eliminated the rest. For example, 够 and 夠 are both pronounced gòu and mean ‘enough’, but only 够 was included in the official set of simplified characters. This helped reduce the total number of characters in regular use.

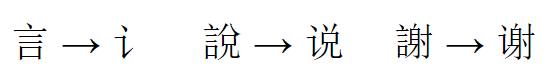

Many other characters were made easier to write by simplifying one or more of their component parts. For example, the radical 言 (yán, speech) was simplified as 讠. Thus, many traditional characters containing the radical 言 were simplified by replacing the traditional form of the radical with its new simplified form.

For this reason, one of the best ways to quickly familiarize yourself with an unfamiliar character set is to learn your radicals. Since many characters were simplified in a standardized way, knowing both the traditional and simplified forms of radicals can help you identify characters in either system. It’s not a silver bullet for decoding every character, but it’s a start.

It’s important to note that most characters have the same traditional and simplified forms. By some estimates, only about 30% of the 3,500 most commonly used Chinese characters today were changed during the simplification process.

If you are interested in the history of Chinese characters, check out The Way of Chinese Characters for an illustrated etymology of how ancient characters evolved into the modern forms used today.

Q: Where are simplified and traditional Chinese characters used today?

Traditional characters are still used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and many overseas Chinese communities. For example, in many Chinatowns in the United States, particularly historic ones, it’s more common to see things written in traditional characters. Even in Mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia, traditional characters are preserved in decorative contexts, like calligraphy, advertising, signage, and--perhaps most importantly--KTV subtitles.

(The sign for Hong Chang Xing Mutton Hotpot, Shanghai’s oldest halal restaurant, is written in traditional characters.)

Simplified characters are currently used in Mainland China, Singapore, and Malaysia. They are also becoming increasingly common in overseas Chinese communities, as more and more people emigrate from Mainland China.

Q: Can users of simplified characters read traditional characters and vice versa?

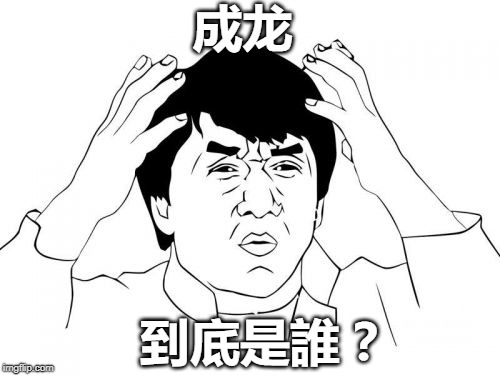

(Jackie Chan, a Hong Kong native, might have an easier time recognizing his Chinese name if it were written as 成龍.)

The existence of two different sets of characters can hinder communication between different parts of the Chinese-speaking world, but it’s not as big of a problem as you might think. After all, many characters are the same in both systems, and for those characters that do have different forms, the difference is often a familiar component, like a radical. That’s why learning the traditional and simplified forms of radicals can be so helpful.

Most educated Chinese speakers have at least passing familiarity with the character set they don’t usually use. Users of simplified characters must know at least some traditional characters in order to read historical documents and other texts written in classical Chinese (not to mention the other decorative contexts we mentioned above).

Even in Taiwan, where it is prohibited to use simplified characters in official documents, many Taiwanese can read simplified characters and use certain stroke simplifications when handwriting. For example, the word “Taiwan” is written in traditional characters as 臺灣, but much of the time, Taiwanese people write 台灣 or 台湾 because it is faster and easier.

It’s relatively easy to convert traditional characters into simplified characters using special software. However, it’s harder to go the opposite way because a small number of simplified characters correspond to multiple traditional characters, and computers can’t yet distinguish the right traditional form from context.

Q: Is it possible to type in traditional Chinese characters?

Of course! Both simplified and traditional Chinese input method editors now come standard with most modern operating systems. In fact, the very first Chinese input method was invented by Lin Yutang in the 1940s for use with typewriters, well before simplified characters were in popular use!

If you do choose to type in traditional characters, however, you might find your choice of fonts somewhat lacking. In the last 15 years, most new Chinese fonts have come from Mainland China, where simplified characters are the norm.

For more information on typing in Chinese, check out our blog post on the subject.

Q: Are simplified characters easier to learn than traditional characters?

Proponents of simplified characters say that having fewer strokes makes it easier to write and memorize characters. Literacy rates did rise dramatically in Mainland China following simplification, but this might also be linked to other improvements to the country’s education system.

Supporters also argue that simplification lends clarity to too-similar traditional characters. For example, consider the traditional forms of ‘book’ (shū), ‘daytime’ (zhòu), and ‘drawing’ (huà).

It’s quite challenging to distinguish these three characters at a glance, especially when written in small font. In contrast, their simplified forms are much easier to tell apart.

On the other hand, proponents of traditional characters argue that simplification created more confusion. For example, in traditional characters, 千 (qiān, thousand) and 乾 (gān, dry) are not at all similar. However, their simplified forms, 千 and 干, are almost identical. Likewise, if you have ever wondered why 面包 (miànbāo, bread) and 面条 (miàntiáo, noodles) contain the character for ‘face’ (面 miàn), the answer lies with simplification. When the traditional character 麵 (miàn, wheat or wheat flour) was simplified, the radical 麥 (mài, wheat or barley) was dropped, giving us 面包 and 面条 instead of 麵包 and 麵条. Arguably, the loss of the semantic indicator 麥 makes it more difficult to understand the meaning of 面包 and 面条.

Proponents of traditional characters also point out that literacy rates in Taiwan and Hong Kong, where traditional characters are used, are much higher than in Mainland China. In addition, the advent of computers and smartphones has made knowing how to handwrite every single character less important. If everyone types most of the time, how much does it really matter if traditional characters contain more strokes?

So while simplified characters might be easier to handwrite because they have fewer strokes, they aren’t necessarily easier to learn. Whichever system you choose to learn, you’re going to have to memorize roughly the same number of characters in order to be able to read things like newspapers and books.

Q: Is it better to learn simplified or traditional Chinese characters?

There isn’t really a straightforward answer to this question--it really depends on your purpose for studying Chinese.

First, consider the kinds of Chinese speakers with whom you are likely to interact. If you expect to communicate mostly with people from Taiwan, Hong Kong, or Macau, or to travel to one of those places, traditional characters may be your best bet. If you expect to deal mostly with Mainlanders, go with simplified characters.

If you want to study Chinese history, art, or early literature, you’ll likely find it helpful to have a strong foundation in traditional characters. If you are learning Chinese to further an interest in business or technology, simplified characters may serve you better. These aren’t necessarily hard-and-fast rules: many historical texts and early works of literature are available in simplified characters, and plenty of science and business is conducted in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau.

Both sets of characters come with their own rewards and challenges. If you stick with learning Chinese long enough, familiarizing yourself with both systems will only deepen your understanding and appreciation of the Chinese language. At the very least, you should learn your radicals.

Comments