From January 1st to January 3rd, Japanese businesses close their doors and families gather together to usher in the New Year in a very special way. Celebrating the New Year in Japan is quite different from the glittering champagne parties of the western world. It is a days-long traditional event which begins several days before-hand and requires extensive preparation.

Preparing for the New Year…

The New Year means a new beginning, and what better way to start fresh than to clean out the clutter of the past year? Beginning around December 30th that’s exactly what families do in Japan. Much like “spring cleaning” in the west, as the year comes to a close, Japanese families clean their homes from top to bottom, a custom known as 大掃除O-souji, or “big cleaning.” According to tradition, all preparations for the New Year must be completed in the three days preceding January 1st, so as not to disturb the gods with the clanging and clamoring of daily household chores (such as banging the dust from bedding or cooking).

New Year’s Eve…

A traditional dish best eaten before midnight on December 31st is 年越しそばtoshikoshi soba (lit. “year-crossing soba”), a long buckwheat noodle symbolizing long-life. Family members gather around the こたつkotatsu on New Year’s Eve to play traditional games (such as双六 sugoroku, カルタkaruta, and 福笑いfukuwarai), watch entertainment specials on TV (most especially the popular annual musical program紅白歌合戦Kohaku Uta Gassen), and await the sound of temple bells at midnight, signifying that the New Year has begun.

New Year’s Day…

The day of New Years is a celebration. Family members get together and visit shrines to pray for peace, health, and safety in the coming year. There are innumerable temples and shrines across Japan, but some of the larger shrines such as明治神宮Meiji Jingu (Tokyo), 伏見稲荷大社Fushimi Inari Taisha (Kyoto), and住吉大社Sumiyoshi Taisha (Osaka) have been known to play host to several million visitors over the New Year holiday.

<image: Iconic red gates of 伏見稲荷大社Fushimi Inari Taisha.>

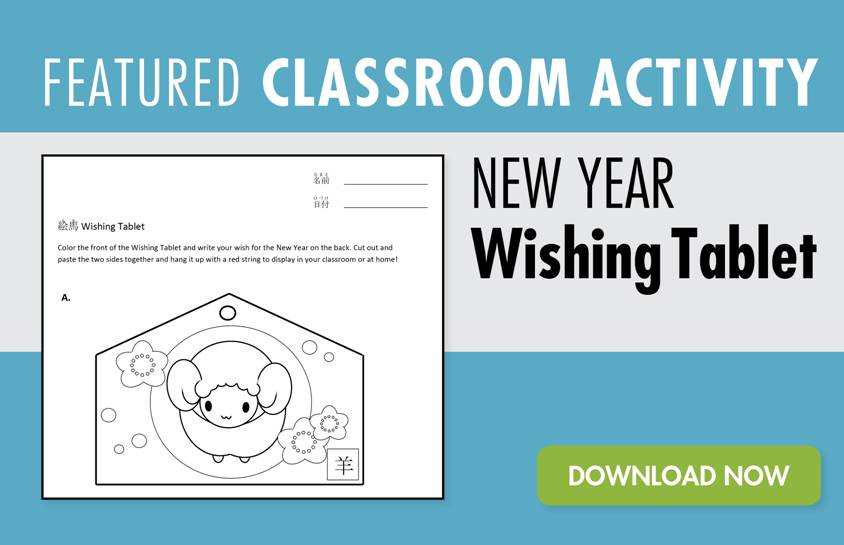

Shrines offer charms for health, wealth, and happiness as well as paper fortunes called おみくじomikuji, which detail the bearer’s lucky and unlucky directions and numbers, among other cautions and prophecies for the New Year. Bad luck numbers in Japan are 四four and 九nine. When pronounced in Japanese, these numbers sound similar to the words for “death” and “agony.” Visitors who draw unlucky fortunes tie them to special trees at shrines so the bad luck does not follow them home. It is also common to write messages and wishes for the New Year on special wooden tablets called 絵馬ema, which are hung on special sign boards at shrines.

<image: Fox-shaped絵馬ema on display at 伏見稲荷大社Fushimi Inari Taisha, a shrine dedicated to fox spirits.>

Upon returning home, families partake in 御節O-sechi, a meal prepared to last for three days in keeping with the tradition of not cooking over New Year’s. Some families even have superstitions about washing chopsticks, and may use disposable chopsticks or a different pair for each meal!

Teaching Tips & Activities:

Expand the learning experience with FREE activities for your class (of any ability level). Download the activities below and create your very own wish tablet, bring the shishimai to life, and expand students’ vocabulary with an extra-special list of words related to Japanese New Year!

Wishes…

Although the tradition of ema is an old one, dating back to the Edo period when shrine-goers would donate horses (the kanji for ema is composed of the characters 絵 “picture” and 馬 “horse”) for their prayers to be heard, nowadays the small wooden tablets can be seen in shrines all across Japan. Most common are ema decorated with pictures of the zodiac animal of the year, but ema can also be seen in the form of popular characters and beloved mascots.

- For lower-level language learners:

Read the history of 絵馬ema above with your class and have them write their own wish for the New Year in English. Color, cut out, and hang the絵馬ema on display in your classroom! Extend their learning experience and discuss the practice of New Year’s Resolutions and ask students to write a brief essay comparing the two traditions.

- For higher-level language learners:

Read the history of 絵馬ema above with your class and have them write their own wish for the New Year in Japanese. Color, cut out, and hang the絵馬ema on display in your classroom! Extend their learning experience and ask them to write a blog post in Japanese about their fictional experience visiting a shrine on New Year’s Day in Japan. Ask the following questions; What shrine did you visit? Were there many people? What did you do before entering the shrine? What are the different ways to offer prayers and collect fortunes?

Festivities…

Among the many festive sights of the New Year is the 獅子舞Shishimai Lion Dance. The dance, adapted from China for the prayer of safety and good harvest, has many regional variations. There are many tales about the Shishimai, but it is generally believe that if bitten by the dragon-like lion, you will have good luck all year long!

Download the PDF and color the Shishimai with your class. Be careful not to get bitten (unless you are in need of some good luck!). Extend their learning experience and show your students a video clip of the Shishimai Lion Dance on YouTube. Ask students to research other traditional dances performed in Japan throughout the year and discuss their significance.

Comments